CYCLE Catalogue essay by Tracy Sorensen

|

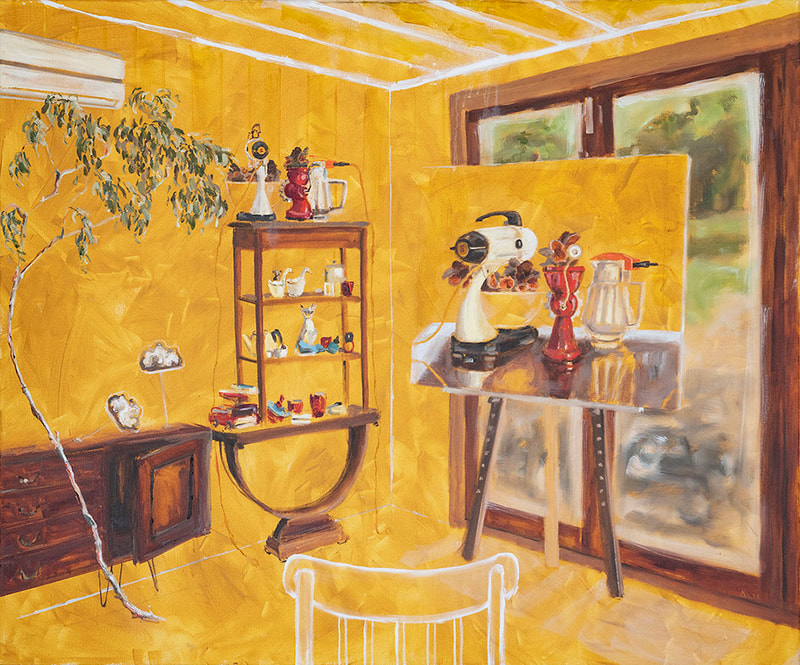

On any given day I will glance up and see three sets of eyes gazing back at me. The eyes belong to two bush stone curlews and a white wallaroo, in two large paintings by Nicola Mason hung in the back room of my house. The bush stone curlews are part bird, part human child, their giant eyes lifted for a moment to regard me, the viewer, before returning to their play. The wallaroo is a more realist rendition, fully animal. It, too, momentarily returns my gaze, perhaps before bounding away. In these paintings, the creatures are outdoors in the Australian bush, where they feel comfortable. By contrast, Mason’s most recent paintings are all set indoors, where humans feel comfortable. These paintings are made in the still life tradition, with objects sitting on a table or flat surface, throwing interesting shadows on the wall behind them. A tiny toy koala rides a duck measuring cup like a horse. A cheese grater and a banksia cone stand side by side, strangers but also strangely familial, like guests assembled for a wedding photograph. Three banksia cones pose with a 1970s kitchen mincer. They’re not in fear of being minced - it seems to me - but behaving more like children posing on the bonnet of a car, enjoying the exhilarating strangeness and power of it. The cones in the mixmaster’s mustard yellow bowl do look a little threatened by the electricity that might at any moment pulse through that yellow electric cord. There are almost-but-not-quite stories here, shades of nursery rhyme and nostalgia, of things endowed with personalities, of the lively relationships that children have with their toys and familiar household things. The move indoors is a familiar one. The pandemic has kept us at home and La Nina, coming on the heels of drought and bushfire, has brought a lot of rain. To make these paintings Mason moved out of her wonky miner’s cottage studio on her small bush property at Napoleon Reef on Wiradyuri country just outside Bathurst, and into the downstairs living space of the family home. As if to press home Mason’s ecological concerns, nature duly made its way indoors, flooding the area. “The weather came inside!” says Mason as we stand in her workspace looking at the paintings and the things - the kitchenalia, children’s toys and plant material - that have been acting as models over this past year or so. Nim the tall kelpie cross and Mr Barry Fox the short collie cross, are also present and from time to time actively participate in the conversation. Two goldfish swim in a large tank on a shelf. Other human family members are lurking in other rooms of the house. Outside, a very old horse by the name of Tiptoe stands in the long grass. Chickens cackle. None of these are extraneous presences. They form part of the flow of biological life that both inspires and requires Mason’s attention. Before she made the decision to paint full-time, Mason had a career in National Parks and conservation management, handling, observing and managing native animals. She is also the mother of three human children. Large parts of her days are spent co-creating and attuning to her family nest. All of this flows into her work. Feminist scholar Donna Haraway calls it situated knowledge, elevating the particular over the general, the personal relationship over the grand, mythologising, “God’s Eye” view. It’s a sensibility that can be neatly contrasted with Sidney Nolan’s epic drought paintings, on show in this gallery at the same time as Mason’s Cycle exhibition. In the Nolan paintings, the dead livestock represent Tragedy and Human Hubris; the dead animals themselves have become almost pure symbol. In Mason’s work, a wombat skull is certainly symbolic, but it also vibrates with the life and death of one particular animal. As it was raining a lot as she painted this recent set of paintings, Mason decided she needed to add clouds. She could have just painted them straight on to the canvas; instead, she played around with creating a small object that could join the others on the table. This is how a painted cloud on a stick came to join the enigmatic relationships of objects/creatures, light, symbol, colour and texture in the series. The banksia cones were found just outside the studio during her art residency at Bundanon, the property gifted by Arthur Boyd on Wodi Wodi and Yuin land on the south coast. Mason guessed they’d been discarded by the previous artist. “There was no wombat poo on them!” says Mason, ever alert to scats in the environment (and the fact that Bundanon hosts a large number of wombats). “It was like when you walk into an op shop and see that thing! Gold!” The banksia cones were attractive and familiar, evoking childhood storylines such as the exploits of May Gibbs’ wicked banksia men. Mason had also seen and remembered the looming life-sized shapes in the soft-sculpture works of Heather B. Swann. Once she’d painted the double shadow thrown by the banksia cone in the red mincer (her lighting set-up includes a floor lamp and daylight), Mason saw shades of a Heather B. Swann banksia looming in the background. The lively shadows in these paintings - their multiplicity suggesting movement - become extra characters at play in the almost- but-not-quite stories being told in these layered images. Part of the story is told by the ground over which the images are painted. For this new series, Mason covered each canvas with a thin layer of acrylic ochre. Wide, energetic brushstrokes are clearly visible, creating abstract shapes, drips and textures. In some of the paintings this ground is almost entirely painted over with layered oil paint, with just small areas of the yellowish ground peeping through. In others, the ground is a bolder presence. “I did the ground first, then when I was painting, I decided to leave it there, to make it part of the composition,” says Mason. “It’s important that the ground is fully playing with the rest of the painting. It makes an interesting play between the abstract and the representational.” There is, of course, an ecological point being made here too: the ground (the land) is never just a venue or a base for our activities; it is an active participant in the creation of the world. The traditional realms of the still life - the symbolic and the compositional - are here brought into dynamic play with 21st century concerns about ecological relationships and the status of the more-than-human world. The combination of organic and manufactured elements (the banksia cone and the cheese grater, for example) blurs the line between what is considered “natural” and what is considered “cultural”. “The banksia cone is a cultural object,” says Mason. “It has been shaped by firestick activity over thousands of years. And the cheese grater is rusting, a natural process.” The combination of such objects as equal players on a level surface creates a slightly unsettling, uncanny feeling. The familiar binary of western sensibility gives way to a non- hierarchical continuum of plants, animals, natural things, human beings and human-made things. Donna Haraway calls this natureculture. While compositional and symbolic aspects are important in Mason’s paintings, these never overwhelm the vital presence of the nonhuman things themselves. Each object seems creaturely, with a personality of its own. The mixmaster, for example, has a black eye on the side of its head, like a parrot’s face seen from the side. The black handle could be the parrot’s crest or perhaps a sturdy quiff of hair. “What’s that word for faces in things?” asks Nic, trying to remember. It’s pareidolia. Our social brains are hard-wired to anthropomorphise not just animals but objects. While some warn against the dangers of anthropomorphising animals and things, its blurring of the strict lines between the humans and non-humans, of culture and nature and objects, is part of the point. New materialist philosopher Jane Bennett would argue that when we’re looking at an old mixmaster we’re not really looking at an “object” at all, but a kind of subject, an “actant” with its own agency in the world. Or, as Donna Haraway says, matter matters. The material world is not a dead thing to be mastered and shifted around at will; it is full of vital, powerful forces that fight back. Like storms and floods, for example. Mason and I look at the things themselves that have done their time as artist’s models and are now taking time off, just sitting around on a shelf in the studio. The mixmaster was once an active working member of the household. The red colander will go back into active service, draining pasta. The small toys lie this way and that, as if resting or dead on a battlefield. “I feel connected to these things,” says Mason. “It’s what’s around me, what I put around me, what I’m interested in.” Tracy Sorensen is a Bathurst novelist and craftivist. She is a PhD candidate at Charles Sturt University, researching storytelling in the Anthropocene. |